Cast your mind back to January 2020. The news was dominated by Brexit, tensions between the US and Iran, President Trump, bushfires in Australia, a volcano in the Philippines and a concerning new disease in China called COVID-19. In just a few weeks, the way that we experience the world would be very different. So, like me, you will most likely have missed a relatively mundane – but super-interesting – snippet of science-related news. The only science covered in any detail by mainstream media related to the novel coronavirus; pretty much anything else was absent. However, among other science news was a study that indicated that you’re most likely a bit cooler than you would have been if you’d been born 150 years previously. The study, published in January 2020, revealed that the average body temperature of humans who live in industrialised nations has been decreasing – and may be continuing to decrease – since the Industrial Revolution [1].

Did 2020 introduce a “new normal” for body temperature? An appropriate phrase for the year in which it’s likely that a record has been set for the number of times people have had their temperature taken. Does 37℃ (98.6℉) apply anymore? Is a lower body temperature something of concern? Is this merely a part of Homo sapien evolution? Or is our coolness related to something else?

Half a Degree … and Falling?

In 1871, physicians Carl Wunderlich and Édouard Séguin, from Germany and France respectively, documented the findings of two decades of Wunderlich’s data from studying millions of human body temperatures. From the research, they established a standard for the normal human body temperature, i.e. 37℃ (98.6℉) [2], a figure that has been used as the medical standard across the world ever since. However, life was very different in the 19th century, notwithstanding the fact that life expectancy (at birth) was 38-40 years back then [3], partly related to infectious diseases like cholera, tuberculosis and syphilis.

Studies over the past 20 years have observed a mean body temperature lower than the Wunderlich and Séguin standard [4]. This posed the question as to whether the observed differences represented a true change in the temperature of humans or a methodological bias. In addition, previous research found that body temperature varies over the course of the day, with a tendency to be higher later in the day, and varies from person to person, with women and younger people tending to be warmer than men or older people, respectively [5].

Myroslava Protsiv and colleagues from Stanford University analysed over 677,000 body temperatures from three different cohorts spanning 157 years of measurement and 197 birth years [6]. They found that men born early in the 19th century had temperatures 0.59℃ higher than men today, meaning a monotonic decrease of 0.03℃ per birth decade. In women, the reduction was 0.32℃ since the 1890s and showed a similar rate of decline. They explained away the reduction as a result of methodological bias and provided evidence for the drop in temperature to be a reflection of physiological differences. They concluded that “humans in high-income countries have changed physiologically over the last 200 birth years with a mean body temperature 1.6% lower than in the pre-industrial era. The role that this physiologic “evolution” plays in human anthropometrics and longevity is unknown.” Moreover, normal body temperature may be continuing to fall.

Why Are We Cooler?

Resting metabolic rate (RMR – also known as basal metabolic rate, or BMR) describes the rate at which the body burns energy during a time period of strict and steady resting conditions. Metabolic rate is a major determinant of body temperature as our metabolisms produce heat as a by-product, and is the reason why we, and other warm-blooded animals, have temperatures within a narrow range. RMR is linked to body mass, and average body mass has increased in Western populations over the last 150 years, and this may be associated with a decline in metabolic rate.*

RMR can be influenced by a number of factors, but a change in the population level of inflammation is a plausible explanation for the observed decrease in body temperature over time. With improved standards of living and sanitation, reduced infection from war injuries (some earlier temperature data was from US Civil War army veterans), improved dental hygiene, reduced infectious diseases, the emergence of antibiotics and the widespread use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are some of the key factors that levels of inflammation may have reduced. Protsiv et al cite studies supporting the rationale behind the different reasons.

Changes in ambient temperature may also help to explain the drop in body temperature. Homeostatic maintenance of body temperature consumes between 50-70% of daily energy intake, and, RMR, for which body temperature is a crude proxy, rises or falls when ambient environmental temperature decreases or increases from the thermoneutral zone, respectively [7]. This may be linked, initially, to central heating becoming more commonplace, and, more latterly, with a higher number of air-conditioned homes.

What Does Being Cooler Mean?

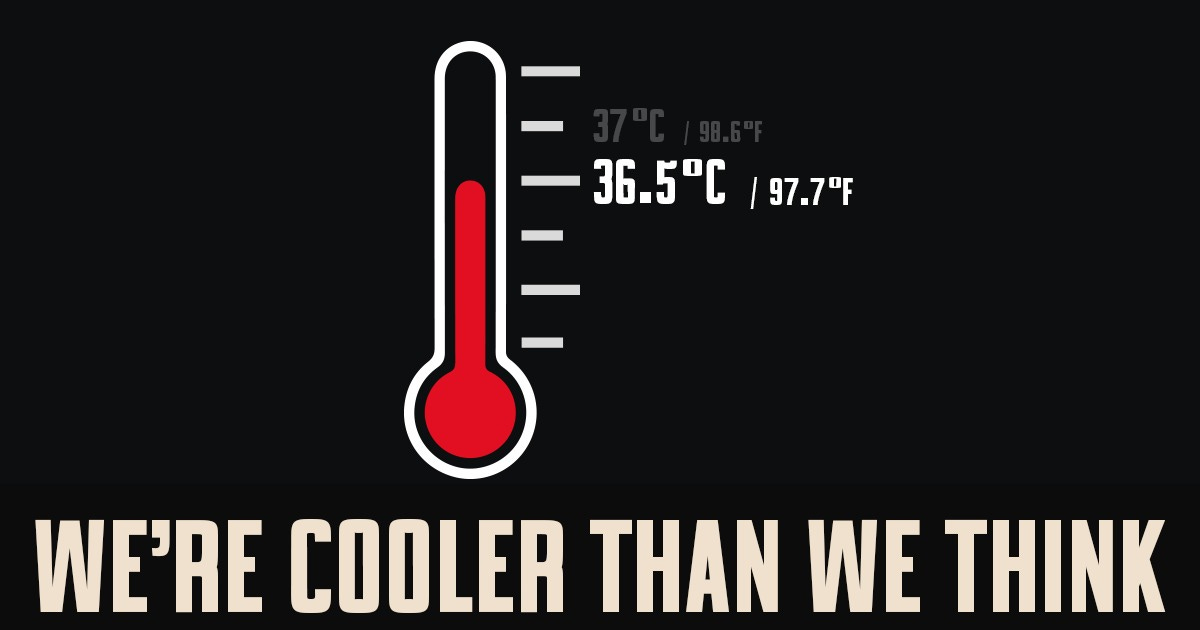

The discovery that the average body temperature for humans in industrialised nations is likely half-a-degree Celsius lower than it was previously, and will likely reduce further, is in no way cause for alarm, but it is interesting, and it could have implications for health policy. Should the standard for body temperature be reviewed to 36.5℃ (97.7℉) in industrialised nations, and how should this apply to people living in less-developed nations?

Most warm-blooded animals have an array of homeostatic mechanisms in play which help maintain body temperature within a tight parameter despite considerable variations of environmental temperature. Too-high body temperature (hyperthermia) can cause dehydration which, in severe cases, can lead to cardiac failure and death, and too-low body temperature (hypothermia) may cause organ damage and death. Body temperature is used in calculating an individual’s RMR, which is used as a measure of working out doses of certain drugs or the nutritional requirements of, for example, critically ill patients in intensive care who need to be nourished via enteral tube feeds. Should formulas like the Schofield Equation be revised based on these findings? [8]

Fever is described as any temperature over 38℃ (100.4℉), and the most common cause of fever is infection, with adverse reactions to drugs being another factor. Taking body temperature is one of the key medical “vital signs” as a quick indicator when evaluating if an individual is sick – although, of course, it’s possible to be sick with body temperature in the correct range. During 2020, the checking of body temperature became a routine entry procedure for many workplaces and hospitality establishments, such as restaurants and hotels, as a raised body temperature indicates a possible infection with SARS-CoV2. Is it appropriate for there to be a revision of the body temperature level for infection, and would this lead to earlier detection of infectious diseases like COVID-19?

* In actuality, it’s a lot more complex and, in some overweight individuals, RMR may increase as a survival mechanism.

(Article originally posted in a Blog on February 8, 2021)

Notes & References:

1. 1. Protsiv, M. et al. (2020) ‘Decreasing human body temperature in the United States since the Industrial Revolution,’ eLife, 9 e49555.

2. Wunderlich, C.A. & Sequin, E. (1871) Medical Thermometry, and Human Temperature. New York: William Wood & Company.

3. Protsiv, et al’s study relates to the USA and stated 38 years. Cross-checked with https://www.statista.com/statistics/1040079/life-expectancy-united-states-all-time/ (Accessed: 7 Jan 2021).

4. (a) Sund-Levander, M. et al. (2022) ‘Normal oral, rectal, tympanic and axillary body temperature in adult men and women: a systematic literature review’, Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 16(2), 122-8. (b) Obermeyer, Z. et al. (2017) ‘Individual differences in normal body temperature: longitudinal big data analysis of patient records.’ BMJ. 359, j5468.

5. Shmerling, R.H. (2020) ‘Time to redefine normal body temperature?’ Harvard Health Blog. https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/time-to-redefine-normal-body-temperature-2020031319173. (Accessed: 23 Jan 2021).

6. ibid (1).

7. Erikson, H. et al. (1956) ‘The critical temperature in naked man’, Acta Physiologica Scandinavica, 37(1), 35-9.

8. Schofield, W.N. (1985). ‘Predicting basal metabolic rate, new standards and review of previous work,’ Human Nutrition Clinical Nutrition, 39(1), 5-41.