“It is useless to attempt to reason a man out of a thing he was never reasoned into.”

- Jonathan Swift

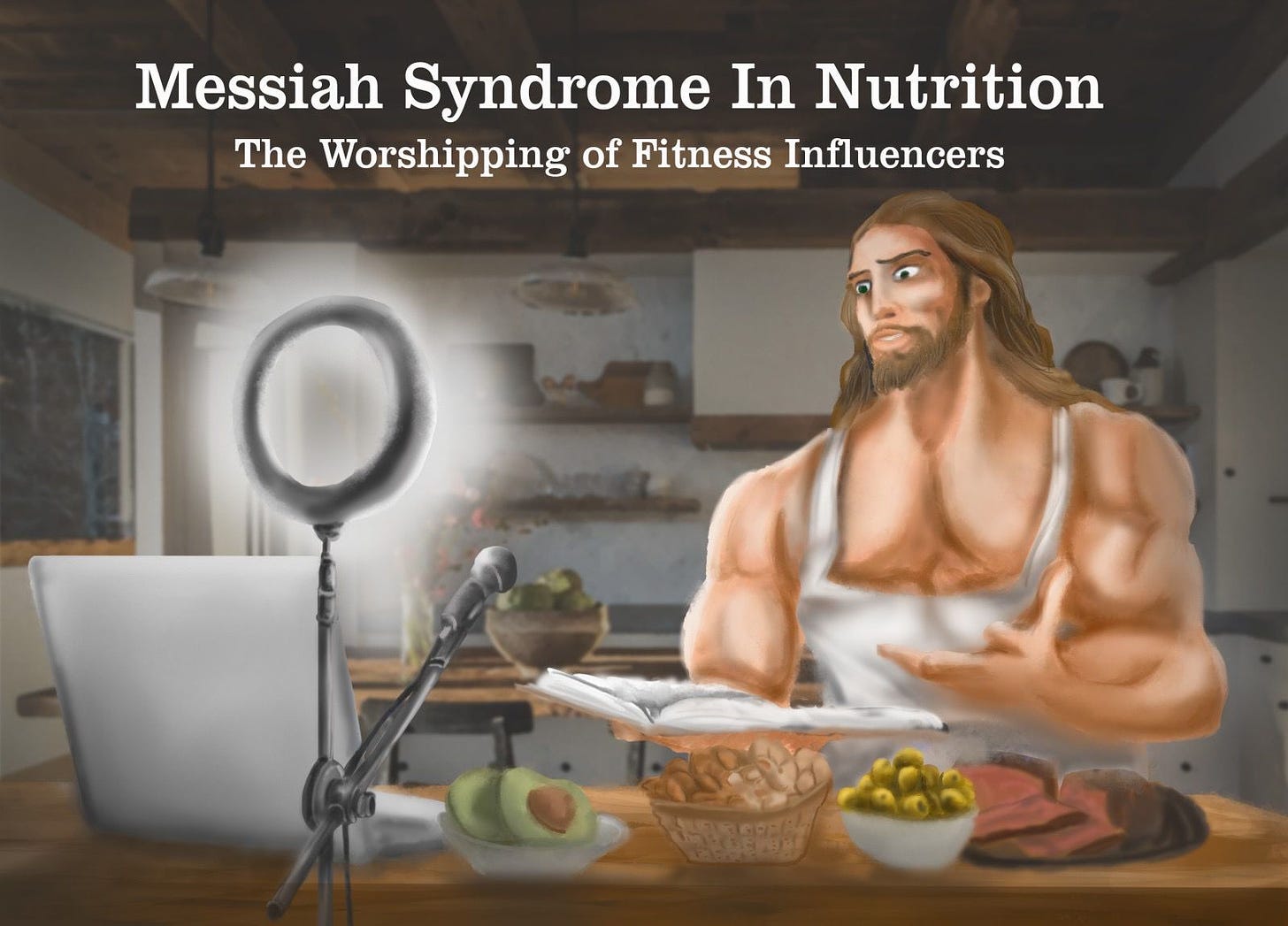

“Change your food and change your life. Respect for spreading the word.” “You wouldn't have nearly 100k followers if you were talking shit.” “You speak the truth! Thank you for all that you do to educate and improve people’s lives.” “This is the only guy in the fitness industry that’s got my attention … because he makes sense.” These are examples of praise lauded in the direction of a fitness influencer who’s recently experienced an explosion in popularity. Who wouldn't want to take advice from someone who draws such acclaim? Now imagine that you are that influencer: every day you receive appreciation and recognition from hundreds of fans. Wouldn’t you believe you were helping people? Perhaps even changing lives for the better?

A brief scroll through Instagram and TikTok reveals an ever-increasing number of content makers sharing their wisdom and diets that, they claim, improve the health of their followers. Encouragingly, there’s a growing number of qualified and experienced nutritionists and dietitians on social media who provide evidence-based, practical tips relayed in a way that’s easy to understand. On the flipside, however, platforms continue to be rife with influencers dolling out dangerous misinformation in the guise of good health. As a nutritionist, I spend time viewing social channels in an attempt to keep ahead of what’s new in nutrition science as well as what’s trending. This includes viewing health and fitness influencers – both qualified and unqualified – with large followings. Of late, one individual – let’s call him Mr M – has provoked concern, both in respect of the content he produces and the way in which he communicates. Mr M has been heavily criticised by several online nutrition experts who, it appears, share my concerns about his pseudoscientific claims. Common traits that run through his videos illustrate characteristics and styles of communication exhibited by other health and fitness content makers with questionable morals.

Easily accessible, alarming health advice is nothing new, of course. Gerson therapy, first developed in the 1920s, involves following a strict organic, vegetarian diet, numerous dietary supplements and daily coffee enemas. Food magazine journalist Jessica Ainscough, a.k.a. “The Wellness Warrior”, disenchanted with the conventional medical treatments offered to treat her rare cancer, opted to follow the Gerson regimen out of desperation. Tragically, Jessica succumbed to her disease in 2015, and experts agree that with medical treatment she would likely still be alive today [1]. More recently in August 2023, fruitarian influencer Zhanna Samsonova died of starvation after following a diet where she ate only raw fruits, supplemented with a few vegetables and seeds [2]. Although extreme examples – the dangers of bad advice from online pseudo-nutritionists are often more subtle – they demonstrate the importance of heeding advice from qualified professionals and snubbing ultracrepidarians.

Before I unleash my criticism, I should point out that some of Mr M’s videos include useful healthy eating tips and recipes that are nutritious and look highly enjoyable. Furthermore, many of the foods he tells people to avoid are those we’d be sensible to eat in moderation, and many of the foods he recommends are nutrient-packed gems and great assets to a healthy diet. Then there are numerous testimonials from people claiming their health has improved from following his advice. So, if many of the foods Mr M tells us to cut out are ones we should avoid, and those he tells us to eat are ones we’d be wise to include, what’s the problem? If people are appreciating his advice, what does it matter if his communication style is a little unorthodox? Is he not providing useful tips that promote health and reduce risk of disease?

Helping, Healing, Educating

In one video Mr M gripes, “The food industry, the fitness industry, don’t wanna hear what I’ve got to say … fitness influencers called me out and I responded.” He appears to think that the reason he’s being called out is because he criticises other influencers’ advice and, consequently, he’s “hurting their livelihoods”. So extreme is his confidence and self-belief that the thought doesn’t appear to occur to him that others might be troubled about the quality of his advice. “If you don’t want to hear what I’ve got to say, move on, but I know I'm bothering a lot of people in the fitness industry,” he grumbles. He certainly is bothering people, but for reasons he doesn’t seem to grasp: his growing following concerns qualified professionals because his advice and that of others like him is dangerous. Moreover, many of the professionals who refute his advice don’t sell products or services, so their livelihoods will be unaffected.

Some who criticise Mr M have pointed out that he makes money from selling his diet and exercise advice services and that the reason he produces clickbait content is to attract people to purchase his services, i.e. his own livelihood depends on him making controversial content. But I’m not so sure. I think there’s something else going on here. While it might indeed be true that he makes an income from selling his services primarily driven by his social content, I’m unconvinced it’s this that primarily spurs him on. It is my contention that Mr M’s motivation to produce shoddy content is a form of narcissism, a disregard for what’s true and a genuine belief that he’s helping people. He has a Messiah complex.

My hypothesis is based on a number of observations. Of particular note is the grandiose behaviour he exhibits in the majority of his videos. For example, he makes statements like, “I know I’m saving lives,” “Listen to me, I know what I’m talking about,” and, “I'm making people feel better. I know that.” In one video he proclaims, “I’m helping people; I’m healing people; and I’m educating people.” This statement is worth looking at. Because in testimonials people have claimed that their health has improved as a result of following Mr M’s advice, we should accept that he is indeed helping some people. It’s likely, however, that these people would previously have been making unhealthy food choices and not exercising, so any improvement in eating habits and increase in physical activity would help them feel better no matter from where they got their advice. Does this mean that he’s healing people? To validate such a claim would mandate the use of objective measurements, such as a comparison of blood markers taken before and after a diet and exercise intervention, and the professional opinion of an experienced medical practitioner who has assessed the subject both prior to and after the intervention. But even this would be of limited validity as it would be a sample size of one and wouldn’t be a controlled assessment, with numerous other factors influencing the results. In the absence of evidence, a social media influencer claiming that he’s “healing” people has no grounding and is, therefore, outlandish, which reinforces my hypothesis that Mr M has a Messiah complex; Messiahs heal people, after all …

What about his claim that he’s educating people? In a video responding to being asked to show the evidence behind one of his claims, his retort was simply, “Do your own research!” Such was the extent of his belief that people should take him at his word. A Messiah has no need to justify himself; we should accept what he preaches on faith. That’s not educating.

Food Shaming and Conspiracism

Mr M has another tactic that fires up his audience: he likes to demonise particular foods; and not just branded products, but also fruit, cereals and other items that humans have been devouring for thousands of years. He warns people to avoid foods which, according to him, “increase insulin” or “cause inflammation”. He uses these and other medical-sounding terms to fearmonger people into shunning foods that, he asserts, “aren’t meant for the human body,” but provides no explanation of the physiological mechanisms behind this claim nor the adverse health consequences.

He attacks nutrition claims on food labels, such as “low sugar” and “high protein”, claiming that brands are deliberately being deceptive to gain sales. Favourite terms of his are “Come on, guys, wake up!” and “They are lying to you!” as if he’s revealing a newly uncovered secret. Companies do, of course, market their products using tactics to encourage people to buy them to get more sales, and, for sure, some of these are ethically questionable methods that we should be concerned about. While more should be done to increase awareness of these dubious approaches, there’s no big secret or hidden agenda here; it’s basic capitalism 101.

Mr M also complains about some ingredients in manufactured products. Brands combine ingredients and use technologies to make products taste nice because they want people to enjoy them so they buy them again. And, not only are recipes created to improve their flavour, texture and appearance, but certain ingredients are added to increase the shelf life of products. Modern innovations in food science have enabled adequate sustenance to be available to people who, until very recently, would have struggled to feed themselves. As well as this, food processing has helped to minimise food insecurity and mitigate famine, allowing billions of people to explore a wider range of foods and glean pleasure from those they otherwise would have been unable to experience. Mr M might make it sound like he’s unravelled some big food industry cabal, but making food taste delicious and marketing products to get people to buy them are things of which we’re all well aware. This is conspiratorial thinking: conspiracists, like Mr M, infer that there’s a group (in this case food companies or the food industry) plotting or acting in secret to gain an advantage (in this case to earn money) immorally. Inferring this is happening without our knowledge and that he’s had a great revelation that he wishes to share is a tactic to lure in followers.

Listen to Mr M and you might think he’s your saviour as he’s uncovered the secret to good health. In his narrative, almost everything boils down to the food choices you make. Heed his advice and your ailments will disappear and you’ll enjoy a long life, free of disease. It’s likely that, at least on some level, he genuinely believes his own commentary, so it’s important to him that people are convinced by his message and, for this reason, his speaking demeanour can be extremely persuasive. Often, his style of delivery is angry: he shouts, points at the camera and waves his arms around in an aggressive manner. These techniques make him a very compelling communicator and go some way to explain his large number of supporters and rapidly growing social media following.

Liar or Bullshitter?

Lying is the purposeful use of a deliberately falsified, manipulative statement with the sole intention of deceiving and to subvert the truth. While, no doubt, a number of online influencers are liars and their motivation is to deceive their audience, this need not be true for those with a Messiah complex. Rather, they are bullshitters. There’s a crucial distinction here. The term “bullshit” was first defined by Harry Frankfurt in his 1986 essay On Bullshit, where he described bullshit as speech intended to persuade with no regard for the truth [3]. This is in contrast to lies where the liar cares about truth but actively intends to deceive. A bullshit assertion may be true, but the motivation is merely to persuade with no care as to whether the claim is true or false. Bullshitting may be a type of lie, but not necessarily. Bullshitters don’t have the same cognitive burdens as liars who have to remember their assertions in order to avoid being noticed. Bullshitters often believe their own statements to be true and have no desire to harness an objective mindset nor an interest in reason. Motivations for bullshitting include persuasion, to influence and to impress.

Mr M is a bullshitter. His goal is to get people to listen to him, to gain as large an audience as possible, to be revered, and to garner acclaim and recognition. He doesn't care if evidence to support anything he says exists, as demonstrated by his rejection of requests to show the research behind his claims. You can’t debate people like Mr M, because, to quote Jonathan Swift, “It is useless to attempt to reason a man out of a thing he was never reasoned into” [4].

Disease Shaming

So far I’ve focused on the credibility (or lack thereof) of pseudo-content makers like Mr M, but what is it that’s so dangerous about the information these zealots preach? Disappointingly, the impact that unqualified social media health and fitness influencers have on people’s health has been poorly studied*. However, shunning foods like fruit, veg, oats and other cereals, and seed oils, could result in people missing out on key nutrients like fibre, essential fats, certain micronutrients and phytonutrients. Although the science of the gut microbiome is in its infancy, we know that it influences our immune health, digestion, cognitive function, mental wellbeing and more, and that the microbes residing in our intestines thrive when we consume a range of different plants. A lot of Mr M’s content focuses on urging people to eat more meat. However, he fails to acknowledge that consuming more animal products would mandate a greater use of intensive and unsustainable agricultural techniques, along with their associated environmental baggage – such as soil erosion and greenhouse gas emissions – and ethically questionable animal welfare. And, of course, meat rich diets are associated with increased cardiovascular disease and cancer mortality [5].

The repercussions of dangerous nutrition content aren’t limited to the physiological and environmental; there are equally concerning psycho-social impacts too. Eating disorders are among the deadliest mental illnesses with cases continuing to rise. According to a systematic review, the global prevalence of eating disorders more than doubled from 3.5 percent for the period between 2000 and 2006 to 7.8 percent between 2013 and 2018 [6]. Moreover, although traditionally cases were far more common in women, men represent a growing proportion, and, despite being classically confined to Western nations, the prevalence of eating disorders in developing countries is on the rise [7]. As well as endowing humanity with improved access to sustenance and a wider range of foods from which to choose, globalisation has been accompanied by more and more people who have a poor relationship with food and a negative self-image. The reasons for this are complex but can be partly blamed on the surge of social media and the misrepresentations inherent in it. Platforms like Instagram and TikTok can be particularly pernicious as, not only do they allow fitness influencers’ images to compel people to aspire to unrealistic goals, they permit pseudo-gurus to dictate what their audiences should and shouldn't eat. In Mr M’s narrative, most diseases – 90 percent, according to him (a figure he fails to quantify) – are the result of what we eat. If you suffer from almost any ailment – from psoriasis to terminal pancreatic cancer – then this stems from you opting to eat foods that are not in line with his diet ideology (but worry not – he can heal you!). In this way, not only is Mr M guilty of food-shaming his audience, but disease-shaming them too. Blaming people for making what he claims to be incorrect food choices, and inferring that they’re responsible for all of their health complaints, serves to further exacerbate the negative relationships people have with food. More concerning still is that this is a cohort that’s highly likely to be viewing this sort of content.

“Stop being so fucking lazy” is a phrase Mr M uses when referring to people who don’t cook their own food using fresh ingredients. He appears to lack any consideration of people’s circumstances. With the growing problem of food insecurity in Europe and North America, an increasing number of people are forced to rely on affordable convenience foods. A worryingly large number of people lack the finances, time or knowledge required to prepare meals for their families. There are single parents working two jobs on top of taking care of their children, and others with depression who lack the motivation to care for themselves, let alone cook a meal. Not everyone has had the good fortune of a stable upbringing with parents who taught them basic kitchen skills. Ideologues like Mr M who fail to acknowledge their own privilege are arguably the most toxic aspect of this sort of content.

Why Mr M?

When looking for an influencer to illustrate my hypothesis, it was easy pickings: the pool of pseudo-bellwethers in the health space who relay their information in a Messiah-esque fashion is vast. But why specifically Mr M? Not only is he, at the time of writing, experiencing a rapid growth in his reach, but he’s widely criticised by other health professionals. Although other quacks would illustrate my point equally well, Mr M takes absolutism to its extreme. He is the fitness world’s answer to totalitarianism.

Unlike other content makers who, when debunking claims, reference the specific video in order to provide a more comprehensible critique, I will not be revealing who “Mr M” is. I’ve no wish to get into an online spat. Recently, when a fitness influencer with a huge following criticised one of his claims, Mr M responded with several derogatory videos in an attempt to discredit him. And when a medical doctor, also with a large following, provided a highbrow evidence-based lambasting of Mr M’s assertions, Mr M’s rebuttal involved him arrogantly shouting at the camera for more than two minutes. The juvenile style of his counter-videos appears to be a defence mechanism: a warning to others who dare to call him out. As well as this, being intentionally controversial and publically rowing with popular influencers is a ruse to gain more followers. He uses strawman arguments like “If you are confident in what you are doing, why are you bothering with my videos? I don’t care about yours. Please stay in your lane and I’ll stay in mine.” These aggressive retorts show that he’s not open to criticism: yet another example of his Messiah complex. While naming Mr M would make it far easier to demonstrate my hypothesis, I have no desire to to be involved in petty altercations launched in my direction. However, full respect to those who produce evidence-based rebuttals against these intellectually dishonest individuals.

Is Messiah Syndrome Correct?

"Messiah complex" is not a clinical term nor a diagnosable disorder, and, for this reason, it’s not addressed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders**. However, the symptoms resemble those exhibited in individuals with delusions of grandeur or with a grandiose self-image veering towards the delusional, or with strong fixed beliefs that appear to cause them stress [8], and with traits in line with those of narcissistic personality disorder. A “messiah” is a saviour or liberator of people and a “syndrome” is a condition characterised by a group of symptoms. Commentators with a Messiah complex display several symptoms: they communicate in an autocratic and evangelical style; display a grandiose and unwavering belief that they are healing people; they fearmonger their audience into shunning things (in this case certain foods) that are not in line with their ideology; they believe others are out to get them and respond to criticism with aggression and strawman arguments, often spoiling for a fight, while failing to grasp that experts call them out because of the dangerous nature of their message; they are untrusting and conspiratorial, inferring that others with nefarious motivations are lying to you but if you heed their advice, you’ll be safe; and they shun conventional science in favour of their own bullshit narrative. They possess the secret: heed their advice and you'll enjoy a long life, free of disease. They are your saviour. And they are egged on by an audience who continually adorns them with praise. If you’re a supporter of an influencer who dismisses science in favour of their own made-up narrative, and you’re failing to critically appraise their information, then you’re following an ideology. You, too, are ideological.

Postscript

Some of you may be thinking I’m somewhat of an ultracrepidarian myself: I’m a nutritionist, yet much of this essay involves cognitive psychology with little in the way of nutrition science. Am I guilty of veering out of my own lane? While such a criticism is reasonable, as outlined in my article How “Hard” Is Nutrition?, “having an adequate grasp of nutrition and dietetics extends well into the psychological and sociological – even the philosophical – realms” [9], and nutrition communication is an integral part of this. It’s crucial for people to have the tools to recognise dietary misinformation in order for them to spot charlatans and instead tune into sensible advice from qualified experts. Is it not the duty of a nutrition communicator to help people learn these skills?

* Actually, this is, encouragingly, starting to be researched in more depth. I’ll return to this in a future article.

** The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, a.k.a. DSM-V, is the fifth and current edition of the standard classification of diagnosed psychiatric and mental health disorders.

References:

1. https://sciencebasedmedicine.org/the-gerson-protocol-and-the-death-of-jess-ainscough/ (Accessed: 1 September 2023).

2. https://www.dailymail.co.uk/health/article-12360065/Dangers-fruit-diet-following-death-vegan-influencer.html (Accessed: 1 September 2023).

3. Frankfurt, H. (1986) ‘On Bullshit’, Raritan Quarterly Review, 6(2), 81-100.

4. Swift, J. (1851) Scientific American, 7, 338.

5. Pan, A. et al. (2013) ‘Red Meat Consumption and Mortality: Results from Two Prospective Cohort Studies’, Archives of Internal Medicine, 172(7), 555-63.

6. Van Eeden, A. et al. (2021) ‘Incidence, prevalence and mortality of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa’, Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 34(6), 515-524.

7. ibid (6).

8. Haycock, D. (2016) Characters on the Couch: Exploring Psychology through Literature and Film: Exploring Psychology through Literature and Film, Santa Barbara, p151.

9. Collier, J. (2023) “How “Hard” Is Nutrition?: Nutrition Science Is More Than Physiology.” Available at https://jamescollier.substack.com/p/how-hard-is-nutrition (Accessed: 1 September 2023).